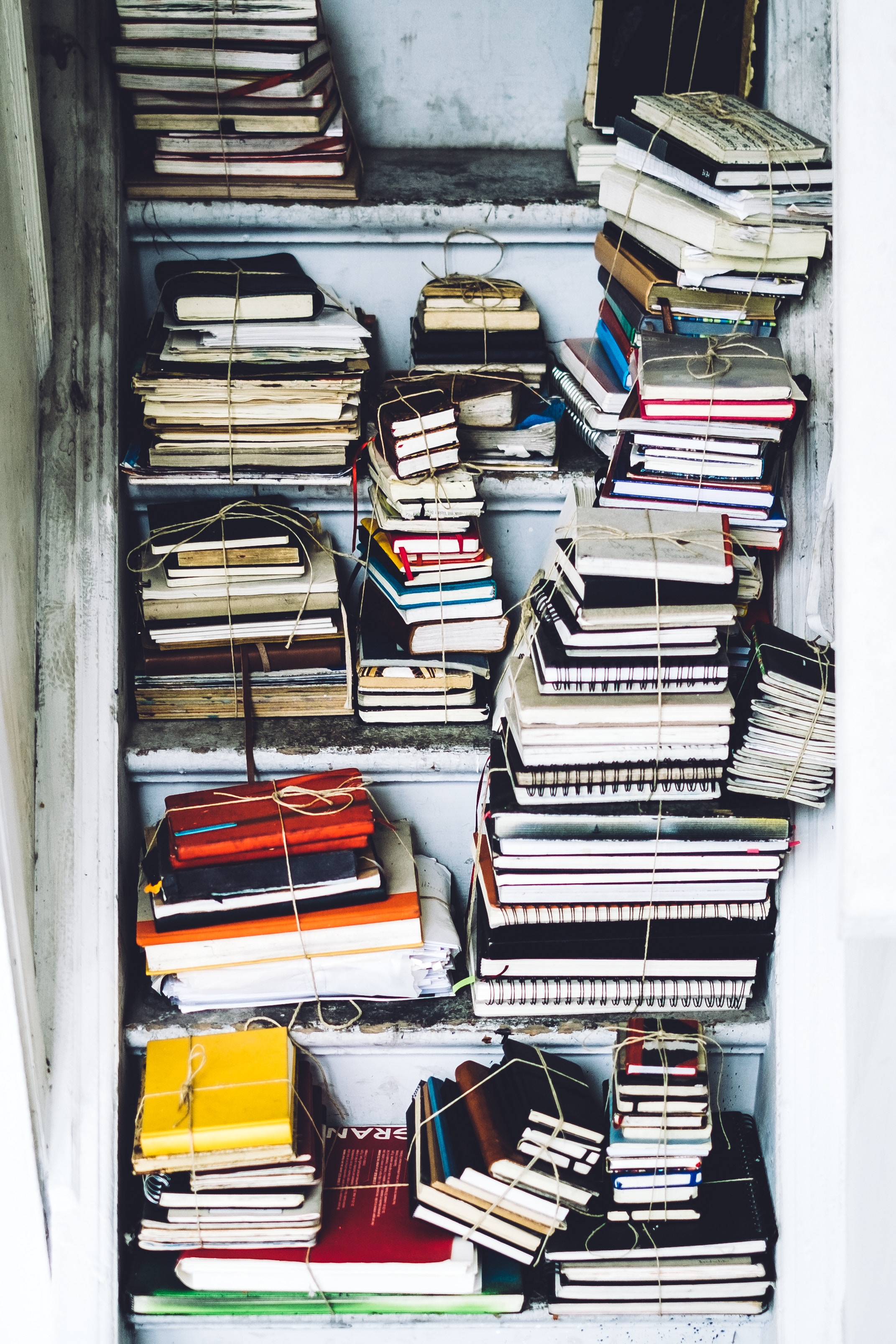

Is it likely that you’ll ever open those old notebooks again? What if you wrote a note to yourself one day in class years ago that would unlock the problem you’re working on today? Photo courtesy @simson_petrol

Year after year the junk builds up. You have documents, you have spreadsheets, and biggest offender of all, you have photographs--endless photographs. More egregious pack rats have video – – lots and lots of video. It’s as if this endlessly compounding digital effluvia has become the new substrate for distant-future petroleum, as if it might someday compress into something viscus and commutable.

The biggest source of this stuff is your so-called smart phone. With the ubiquitous, easy to use digital capture device in your pocket, it’s natural to fire off shots whenever and wherever. Since you’re never going to run out of film, the inclination is never to toss anything either. Lucky for you, storage costs have plunged in the past 10 years, with promises for continued cost reductions. Phones carry more memory than ever before and cloud-based solutions are easy and cheap to access.

Naturally, the vast majority of these snaps do not rise to the heights of Ansel Adams Half Dome. It’s unlikely that you will even casually peruse most of the images and video clips you capture beyond a quick swipe through your photo stream. The shelf life for these images is fleetingly short, and their fissile power to spark future feelings exceedingly small.

Nonetheless, your storage space fills at an extraordinary pace, and when you ponder a wholesale house cleaning, you’d rather do anything else. Why take the time to clear out storage space when it’s so easy to find more?

“Cruft” is a word from the early days of computing that describes accumulated junk that never gets deleted from bloated code. The term applies to the non-code world, too, now largely referring to the digital driftwood that accumulates on all of our many devices and cloud storage spaces.

Once in a while I’ll convince myself to take ten minutes and clean out the most obvious wastes of space. When there are photographs that I clearly never intended to take – – say, a blurry shot of my feet while extracting my phone from my pocket – – I’ll think of purging it to save space. No single misfire will empty much, but my thinking is that a rigorous purge of all sorts of flotsam will relieve storage space useful for better purposes. Do I really need 12 nearly identical shots of a birthday cake?

Inevitably my finger hovers above the trashcan icon. What if that seemingly irrelevant shot, blurry and showing no discernible subject, is the downstream neurological spark of some elegant surrealistic moment? What if by ejecting my mistakes I am ejecting the seeds of future inspiration? The challenge of discarding what we create carries potentially mortal consequences for future invention. When the Brazilian national museum went up in flames in 2018, carrying 20,000,000 artifacts into the atmosphere in the form of smoke, a profound, irreplaceable legacy of culture disappeared. What if a similar phenomenon happens in a microcosm every time I tap “delete” for a photograph or a note-to-self?

Everything is not equivalent. Every click of the electronic shutter, every document capturing a handful of words, and every pencil sketch of a new sculpture yet to be shaped does not constitute art. What’s more, the ease of preservation has threatened to bury all good ideas under mountains of irrelevancy. Even worse, the mountain of irrelevancy has de-valued ordinary good ideas simply because mediocre ideas can overwhelm the conversation.

Still, my finger hovers over the delete key.

The value of saving everything isn’t so much the value of any individual document or photograph. A “save everything” strategy preserves a state of being, a temporal snapshot of the creator’s behavior as much as it preserves the item itself. I hesitate before deleting because we are all unable to go backwards in time, to replay the recordings of our earlier lives. But saving everything can cause all sorts of trouble. Saving everything makes good signals less recognizable amid surrounding noise. Deleting things without care removes context around the valuable stuff, tenuous though that context may be.

There’s no perfect strategy about preservation. A present without a past promises no future. A future buried under the past dulls the senses today. For an artist, the eternal balance is in finding the focus to create while navigating a simultaneous loss of memory and a clatter of infinite remembrances.