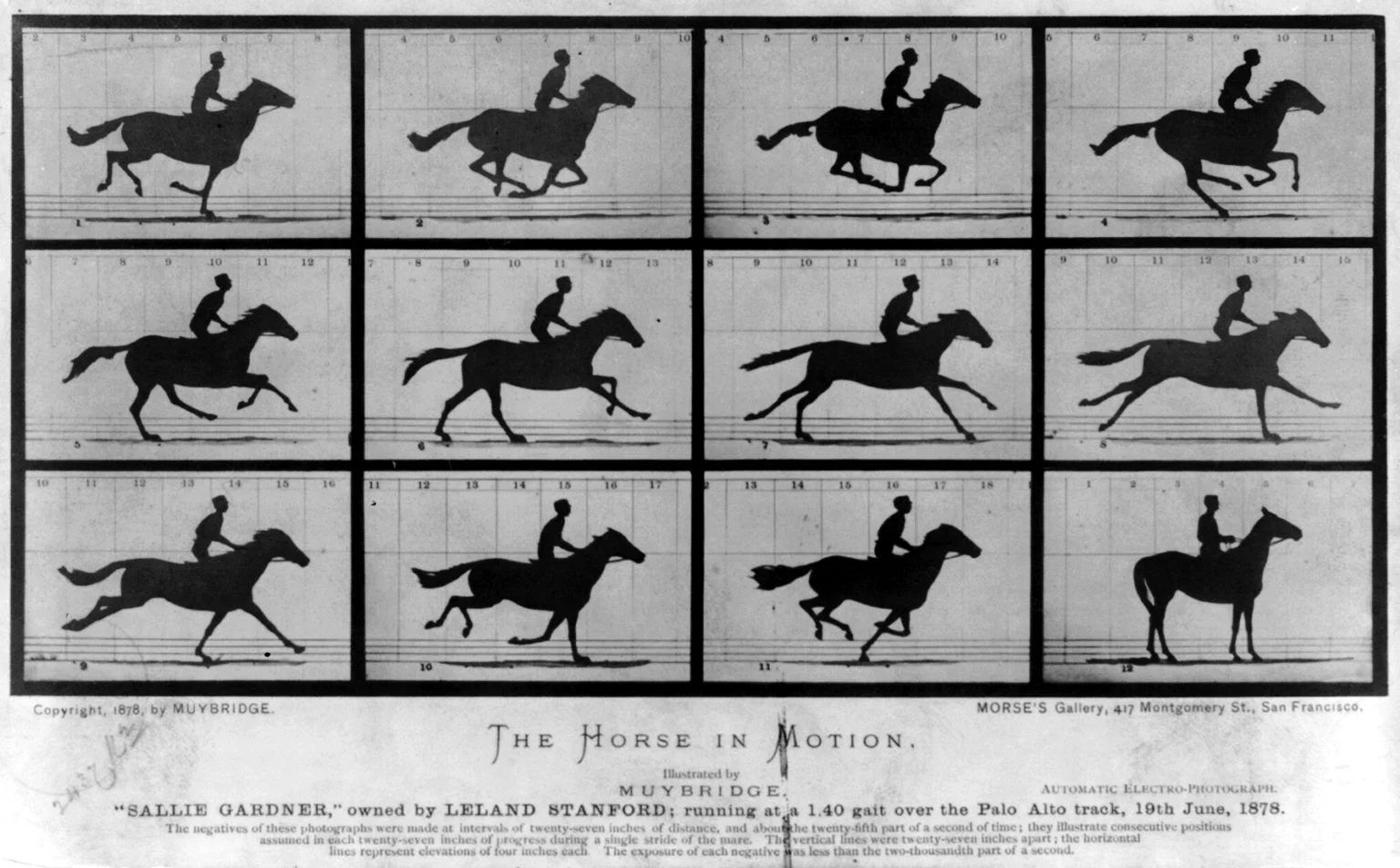

Early high speed photography required a manipulation of conventional rules, like multiple cameras being triggered in sequence in this 1878 collection.

In the early days of cinema, special effects by themselves were essentially magic tricks designed to delight audiences. But it didn’t take long until those tricks started to become narrative story elements. Shortly into the twentieth century we all willingly gave ourselves over to the notion that Glenda the Good Witch travelled to different Oz neighborhoods in iridescent bubbles. Her arrival and departure didn’t trouble us; we accepted her bubbles as part of the story. (I must confess, however, that I always wondered where she went when she wasn’t on screen.)

These deceptions got better and better over time, with countless demonstrations of impossible phenomena becoming common parts of the storytelling experience. Gunslingers didn’t die in Western shootouts and spaceships didn’t jump to light speed, but we all quickly learned to accept these depictions as real in order to experience the stories that used them.

So far, there’s nothing new here. We’ve been delighted by deceptions in the service of story for centuries. Theater has been presenting illusions to audiences since ancient times. Did you ever give a moment’s thought to the body count in Romeo and Juliet? After death, all the actors come back to life for curtain calls.

The difference between everything that’s come before and the last two seconds (relatively speaking) is that media now shows us things that were otherwise invisible, as opposed to made up. We now seamlessly blend our intake of special effects—impossible events, like superheroes flying over skyscrapers—with otherwise unseeable events—things like slo-mo, high speed, and highly dynamic color correction. We practically expect it, demand it. We count on augmented experiences that transcend our unassisted human abilities, and we feel like there’s something unsatisfying if our media experiences don’t show us physics-defying phenomenon.

These are not visuals that have been specifically invented, although in the pursuit of their presentation they are no less imagined and hand-made. But they are things that might otherwise have gone unnoticed, as opposed to purely fabricated. They are depictions of heightened realities, and they are profound in their implications. We know we’ll never see a caped hero leap tall buildings in real life, so we immediately accept it as authentic to the rules of fictional depictions. But a time-lapsed sunset tells us something else. It tells us that we’re outside the story. It tells us that the hand of the story’s creator is present, manipulating time and space. Rather than ask us to suspend disbelief, it tells us to watch what the content creator can do. It keeps us separated from story, rather than drawing us in.

Recall how it used to be. Without technological boosts, people generally observed events from static vantage points. We stood on our own two feet and we saw things, heard things, felt things with our senses. If we were walking while we were watching, we’d feel a familiar beat to our feet on the street. Generally speaking we saw the world from perspectives that we could achieve with our own bodies placed in ordinary space.

Not anymore. These days we’ve come to expect slowly drifting cameras, moving points of perspective, and shifts of focus. We hardly ever look at modern media without expecting some sort of added context and dramatic notes to whatever it is we’re observing.

But that’s just the beginning. Transformations in temporal organization, namely slo-mo or time-lapse video, are now commonplace ways of abstracting the “real” world to let us know that we’re some place worthy of special treatment. These days we routinely experience reality through a conscious filter.

Even color has turned into a subjective state. In what used to be the province of only highly skilled pros, the masses can now routinely massage images and videos to finesse nuances in tone and shade and texture. Show me a mainstream image, and I’ll show you a carefully manicured collection of pixels.

This phenomenon exists even for audio. Rarely do we experience the sonic world as if we were physically in a place when events happened. Sounds get directed, mixed, equalized, and filtered. Beyond purely imagined aural ideas heard in sound effects, our audible perceptions of sonic reality are all about someone else’s augmentation and embellishment.

This would all be little more than a fascinating exploration into the world of contemporary media trend-spotting and fashion—a modern quodlibet, in other words—but there are consequences. With everything now presented as a stylized, amplified reflection of reality, the real world doesn’t have the snap and sizzle of our re-created versions.

Art has always been about fantasy, even if that art masquerades. Van Gogh showed us the night sky through the painted filter of his imagination. In the dazzling beauty of Starry Night, we experience the desire for exuberance expressed by abstraction. In the pain of life, Van Gogh’s refraction becomes our intense pleasure.

We experience similar manipulations when Mozart carries us to Hell along with Don Giovanni in the second act amid a whirlwind of blazing strings. In the protagonist’s comeuppance, we not only understand the moral allegory of fantasy, but also the sly, courageous stand the composer takes against our inevitable, fragile mortality.

No doubt there’s ample room here for debate, especially considering the fungible boundary between what we manipulate and what we outright imagine. What separates these older artistic expressions from modern trends is that they take place right in front of us. They may use imagined sights and sounds to convey sentiment and concept, but they do not trade in perceptions outside of our unaided senses. The modern trend, conversely, trades in the opposite. Rather than Don Giovanni opening his door to find a character representing a thematic idea, we might expect a desaturated color palette to wash the stage while a crimson spotlight limns the Commendatore as he implores Don Giovanni to repent. Rather than abstracting the world (that’s theater) we would stylize it.

With a ubiquity of tools these days, millions of people who might never have considered creative pursuits are suddenly pumping out new content. But just because everyone can manipulate time and space does not necessarily make the collective trend constructive. It’s one thing to comment about the reality of life through art; it’s another to simply yammer. When the real world is no longer adequate for exploration, the real world loses its currency and value. When the dominant style of expression in contemporary media is manipulation of reality versus genuine imagination, we risk an erosion of deep values and a tendency to float in superficial breezes. When manipulation supplants imagination, we begin to lose our tether to meaningful observations and astute cultural analysis.

Modern media tries hard to present a reality that transcends ordinary experience. We delight at slo-mo video because we fantasize about the ability to live in such luscious time, as if we could reach in to that impossible slow-down moment and adjust the pell-mell momentum of events. Even if slo-mo video shows beautiful cascades of spilled milk crashing in white waves onto a pristine kitchen floor, we delight in a common recognition. In slow motion video we don’t have to worry about what any of it means, but we also don’t have to worry about cleaning it up.